- Are your investments well diversified?

- Do they align with your personal risk profile?

- Do they cleverly optimise risk and return?

- Are you a believer that time in the market beats timing the market?

Best practice investing encompasses these ideas today, but these ideas did not emerge by chance. Let’s reflect on some key investment principles and the people who have enhanced our collective understanding of investing.

Harry Markowitz and Modern Portfolio Theory

In 1950s Chicago, Harry Markowitz changed the way we approach investment decisions with his introduction of Modern Portfolio Theory, and particularly the efficient frontier. This curved line on a chart represents portfolios with the optimal balance of risk and return. His work demonstrated that by combining assets with various levels of risk, investors could construct a portfolio that balanced risk and reward more effectively than simply investing in individual securities. This something that every ‘balanced’ superannuation and investment fund in Australia aims to achieve.

Eugene Fama and the Efficient Market Hypothesis

Fama conceived his Efficient Market Hypothesis in the 1960s; the idea that markets are efficient if all investors possess the same information. This seems far more likely in the age of the internet than in the 1960s. In an efficient market, stock prices are always a reflection of their true value, and the market does not misprice assets. This challenged the idea that stock-picking or market-timing, could consistently add value.

The popularity of index funds and ETFs that aim to replicate the market rather than beat it, reflects this approach. However, the theory assumes markets and individuals act rationally, which isn’t always true for humans.

Kahneman & Tversky and Behavioural Economics

In 2002 Daniel Kahneman won a Nobel prize for Economics despite not being an economist. He and his research partner Amos Tversky were psychologists, who together laid the foundation for behavioral economics. Behavioral economics challenges the notion that individuals make rational choices.

Their research identified biases and heuristics (mental shortcuts that people use to make decisions) that cause even the most intelligent people to make irrational decisions. These include:

- Loss aversion: Individuals experience losses around twice as intensely than an equivalent gain.

- Availability bias: People overestimate the likelihood of events based on how easily examples come to mind. For example, people tend to overestimate the frequency of dramatic events like plane crashes, shark attacks and market crashes because they’re memorable.

- Anchoring occurs when individuals rely too heavily on initial information when making decisions. A $1000 pair of shoes, reduced to $300 sounds like a great deal, regardless of the real value of the shoes. In 1999 around 1.8 million Australians purchased shares in the Telstra 2 float. The price was $7.40. Many people are still holding the stock, waiting to get their money back (it has not traded at that level for over 20 years).

These biases can lead to irrational behavior at a broad market level, and for our own individual decisions. It is easier to identify these biases in other people’s choices rather than our own. Financial advisers offer a useful sounding board to ensure that the decisions we make are indeed in our best interest.

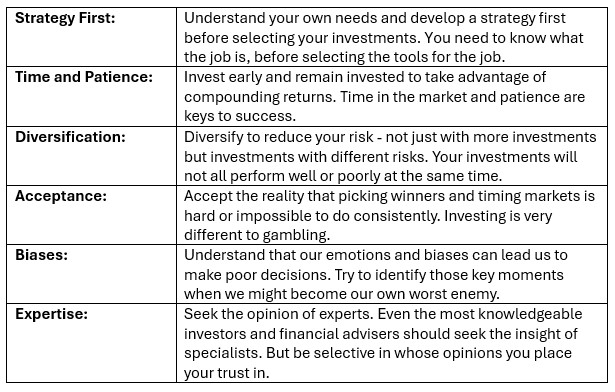

So, with decades of investment research and wisdom behind us, we can each build a personal investment philosophy around these concepts.